Requeening Reconsidered

21 June 2024Article written by Phil Godman, Biosecurity Tasmania Of all the factors affecting the productivity and behaviour of a beehive, none is more significant than the queen bee herself. A vigorous, […]

Article written by Phil Godman, Biosecurity Tasmania

Of all the factors affecting the productivity and behaviour of a beehive, none is more significant than the queen bee herself. A vigorous, well-bred queen can be the difference between a colony of nasty hot-tailed pests and a quiet group of honey-gatherers, increasing their (and the beekeeper’s) wealth. It can also be the difference between a hive always on the verge of swarming and one with low swarming tendencies.

Ever since beekeepers have learned that queen replacement was possible, they have worked on improving stocks. The question remains of when to requeen, both in terms of the queen’s age, and best practice biosecurity outcomes.

The advent of Varroa necessitates reconsidering all beekeeping operations and re-queening is no exception, especially here in Tasmania, where current varroa-related import restrictions do not permit the import of queen bees from interstate.

Historically, wing-clipping and marking were used to show a queen’s age, but for many beekeepers it has become common practice to replace queens every year.

One significant factor regarding the timing of requeening is the swarming season. Queen rearing cannot succeed until mature drones are available, so the commencement of swarming (usually October in Tasmania) informs the beekeeper that drones are in the area and breeding can begin.

So, should a beekeeper always replace queens at this stage? Many have routinely replaced queens in Spring, as a young queen is a major factor in stopping a colony from swarming, thereby reducing pest and disease spread. However, if Varroa is present, the timing of requeening becomes even more critical.

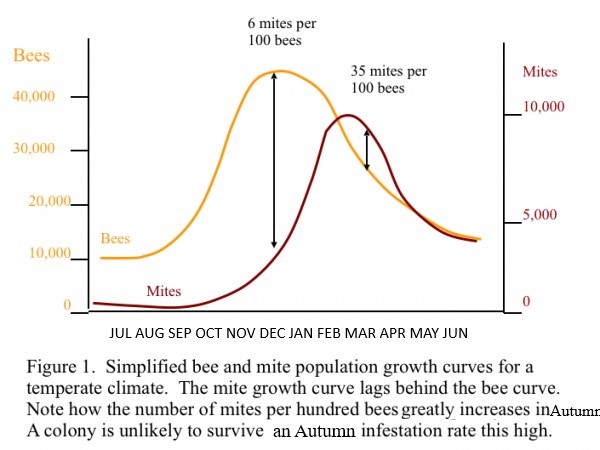

Consider a colony with Varroa that starts the Spring with a moderate mite count. As the amount of brood naturally increases, the mite count too increases. Following the Summer Solstice, when bee breeding drops off, the mite count continues to rise exponentially. Without intervention, by late Autumn the colony would be so badly infested they would be unlikely to survive.

What tools do we have in our Integrated Pest Management toolbox to prevent this? Chemicals, of course, but we cannot rely solely on them. Removing trap-drone comb can also help reduce numbers, but the effect of a break in brood rearing can be most effective. When the hive is queenless, it can take up to 4 weeks to raise a mated queen and during this time, mites have no opportunity to enter developing cells. When the brood rearing re-commences, if many mites enter the brood cell in competition, the pupa will likely not survive: as a result, all starve, and no mite breeding takes place.

Simply caging the queen for several weeks would have the same effect, but not provide a new young queen.

Limiting brood-rearing in the Spring is not in a beekeeper’s best interest, but after the Summer Solstice, egg-laying naturally reduces anyway. Tasmania’s major honey flow is over about March, so a late Summer/early Autumn brood break would have negligible effect, with the added advantage of a young queen, which will come out of winter, ready to go.

Thus, to raise queens in the tail-end of the honey season can be a tool to break the exponential growth of mite numbers. This would provide a queen which would lay more brood in Autumn, increasing hive strength going into Winter, and still be a strong young established hive mother in Spring. As Varroa forces beekeepers to reassess their business operations, this is a good opportunity to reconsider your requeening practice.

Biosecurity Tasmania delivers the Tasmanian component of the National Bee Biosecurity Program (NBBP) and provides significant co-investment and expertise. The NBBP is coordinated by Plant Health Australia and funded by the Australian Honey Bee Levy.